Children are amazing at asking questions that are difficult or even impossible to answer. They ask “Why?” repeatedly.

Children are amazing at asking questions that are difficult or even impossible to answer. They ask “Why?” repeatedly.

Child: Why do we live in Belmont?

Mom: Because after your Father and I got married, we decided this was where we wanted to live.

Child: Why did you want to live here?

Mom: Because we liked that it was close enough to the city but also quiet and peaceful.

Child: Why did you want to be close to the city and in a quiet and peaceful area?…

We can apply this child-like curiosity to our own lives as adults. By asking why, we are challenged to go deeper and deeper to find answers that are near to our purest motivations. Not only on an emotional level, but even so far as looking at how we move. We can apply it to the origins of movement in biological life. In doing so, we can ask the question, “why did we start to move?”

As a both a teacher and practitioner of movement, there are fundamental questions that I explore to inform the work that I do. Two of these questions include:

- Why did the brain evolve?

- Why did movement evolve?

This blog post will briefly explore those questions from the perspective of one of my favorite modern day thinkers, Lisa Feldman-Barrett, a neuroscientist and psychologist at Boston University, who is most well known for the theory of constructed emotion. She builds on the findings of neuroscientists, Peter Sterling and Simon Laughlin at MIT.

Why did the brain evolve?

According to Feldman-Barrett, “All brains accomplish the same core task: to efficiently ensure resources for physiological systems within an animal’s body so that an animal can grow, survive and reproduce.”

In short, our brains are wired to ensure we have or get everything we need to thrive. In order to do this, the brain forms what is called an “internal model” that maps both the external and the internal environment.

We have sensory mechanisms, known as exteroception and interception, which monitor what is going on both outside of us and inside of us. Outside of us, we might be sensing the temperature of the air, the color of the clouds, the texture of the walking surface, or the attractiveness of a potential partner. Inside of us, we might be sensing the discomfort in our lower abdomen, the warmth in our hands, the thumping of our heart, or the location of our femur relative to our pelvis.

All this information is collected in an attempt to make accurate predictions about how to behave. For example, if we sense that a particular area is dangerous to us, we will avoid that area. In contrast, if we sense that an area is safe, we will move towards it. Over time, we form habits that will often constrain our experience to what is “safe” or comfortable. This map is not etched in stone. If we accumulate new experiences, our brain can update its internal model to account for more information. It can then use this information to make more efficient predictions about how to grow, survive and reproduce in the future. I would also venture to suggest that you can use this same process to learn how to reach our fullest potential.

Why did movement evolve?

According to Feldman-Barrett, “Metabolic and other expenditures are required to plan and execute the physical movements necessary to acquire those resources in the first place (and to protect against threats and dangers).”

In simpler terms, movement is one of the means by which biological organisms maintain themselves. In more complex terms, movement is one of the means by which biological organisms maintain “allostasis”, which is a process for regulating the body according to an internal cost benefit analysis.

One of the classic predicaments that an organism needs to manage is between energy usage and energy consumption—burning calories and eating food. In today’s day and age, most of us no longer have this predicament. Our industrial food system makes it easy for us to acquire energy resources. We only need to walk down to the convenient store or market.

In a term popularized by the Harvard evolutionary biologist, Daniel Leiberman, we are in an “evolutionary mismatch” with our environment. This is a contributing driver of conditions like heart disease and type 2 diabetes.

We are mismatched because our nervous systems evolved to efficiently manage our resources, but this happened in an environment where resources were scare and not abundant. In a developed country like the United States, abundance of calories is the norm.

Why is this relevant?

The underlying reasons for how our brain and movement evolved is important to understand because it informs us about our human condition.

In one of my favorite articles ever written on exercise, Leiberman writes, “All in all, humans have these deep-rooted instincts to avoid unnecessary physical activity, because until recently it was beneficial to avoid it. Now, we judge people as lazy if they don’t exercise. But they’re not lazy. They’re just being normal.”

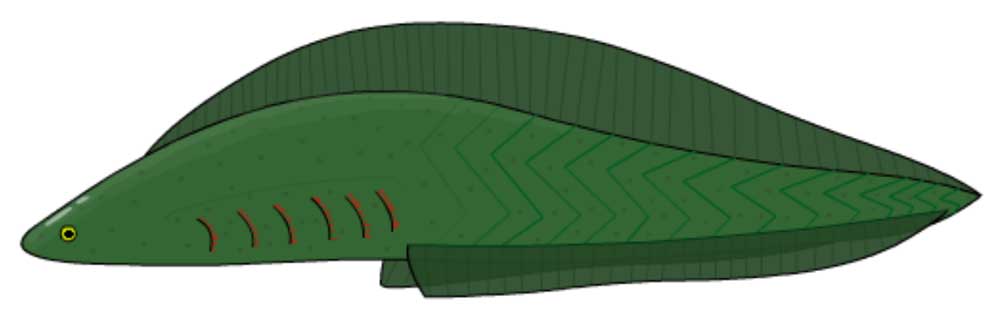

Myllokunmingia

As humans, we can often blame ourselves for our own shortcomings without ever realizing, that from the very beginning, the cards were stacked against us. The research that investigates the development of early brains and early movement in vertebrate species extends all the way back to over 500 million years ago. These little creatures are known today as Myllokunmingia and if you use your imagination, you can see how we evolved from this life form.

The basics are all there—namely the rudiments of a brain and spinal cord. Eventually, these organisms would develop the foundations of terrestrial locomotion—upper and lower limbs- and crawl out of the ocean to inhabit the land. As best we can currently theorize, these are our ancestors. Understanding who they were and how they developed is understanding who we are, how we developed, and why we are the way we are.

In a future post, I will tackle Feldman’s original ideas around what emotions are, how they developed, and why this is relevant to movement practice and bodywork. If interested further, please reference the links below.

Resources

- https://www.affective-science.org/pubs/2017/barrett-tce-scan-2017.pdf

- https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2021/01/daniel-lieberman-busts-exercising-myths

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myllokunmingia